Our take: 5 day trek in the Simien Mountains

The following article appeared in the September / October issue of the Adventure Travel Magazine and was written by our Ethiopia specialist Ben. It gives a great insight into what to expect on a trek in the wonderful Simien Mountains of Ethiopia.

Dust ruptured into clouds as the old Landcruiser took us from the medieval City of Gonder to the Simien Mountains. The landscape seemed intensely dry. Hoards of goats and cattle scratched after the last remaining roots and tufts of golden grass. This was the first time I had left the cities in Ethiopia and what a contrast to the metropolis. Grubby kids ran from primitive wood huts to stare at the 'farenjis' who had come to walk in the Simien Mountains. In Ethiopia you don't walk for pleasure, you walk because you have to.

It was market day and floods of people carrying bundles of firewood, cow hides and sheep were headed into town - the crowd parting as we struggled through. Finally, after five hours of rutted dusty roads, we reached the mountains and with great relief set off on foot. Waiting for us was a huge view. 800m below and stretching towards the horizon lay the lowland mountains that cover such a vast swathe of land in Northern Ethiopia - it was a view we were to get very used to.

It was market day and floods of people carrying bundles of firewood, cow hides and sheep were headed into town - the crowd parting as we struggled through. Finally, after five hours of rutted dusty roads, we reached the mountains and with great relief set off on foot. Waiting for us was a huge view. 800m below and stretching towards the horizon lay the lowland mountains that cover such a vast swathe of land in Northern Ethiopia - it was a view we were to get very used to.

Ask most British people what they know of Ethiopia and they will tell you about the famine and Bob Geldof. Wander through the main cities though, and this view is hard to reconcile. Ethiopia is a country divided, divided by tribes, divided by religion and most pertinently divided by economy. 70% of Ethiopia's population are rural subsistence farmers, whose children help herd the family livestock from a very early age and whose precarious existence depends on the annual rains. By contrast, the urban middle class is growing fast, education is good and there is an unexpected sense of calm and order. Addis Ababa, the capital, hosts the African Union and a large number of NGOs. It has two world class museums, and a number of fantastic restaurants. So it isn't until you leave Addis behind that you start to get a feel for how the majority of Ethiopians live. This is where the Simien Mountains step in.

The Simien Mountains National Park lies at an altitude ranging between 3000 and 4500m. It is a relatively small slice of a huge mountain range and there is pretty much one trail that runs through it with various extensions for those with the time and energy. The trail passes along an incredible ridge and must offer the highest ratio of views to km anywhere in the world. Golden grasslands roll towards the precipitous drop and lowland mountains stretch towards the horizon. The superb wildlife is a huge feature. We'd heard tales of the rare gelada baboon, wallia ibex and Ethiopian wolf and even the elusive leopard. Our 5 day trek was to take us along the line of the ridge from our first camp at Sankaber at 3,230m to our final camp at Chennek 62km away. Along the way we'd be topping summits at Imet Gogo (3926m), Inatye (4070m) and Mount Bwahit (4,430m).

The crew for our trek was generous. In support we had our guide Tesfaye, our scout Adem, a chef and a chef's assistant - four people before you count the team of muleteers. Tesfaye had in all likelihood swallowed a birders handbook at birth and his English was excellent. Adem spoke no English, but his protective nature and toothy smile more than made up for it. All trekkers have to take a scout. The scouts are drawn from former army scouts who live in the area. Their job is to protect you and your belongings. Adem carried an old Russian rifle that deserved antique status. I nervously asked Tesfaye if there had been any trouble to justify the gun?

"Well not really. 2 years ago a bandit tried to steal from the camp, the scout fired a warning shot and he fled."

"So why the guns?"

"It is difficult to answer, everybody asks that question."

"And what do you answer?"

"The scouts helped protect the park during troubles. Employing them is returning the favour"

"But why do they need to carry a gun?"

"Well, Ethiopians like carrying guns" changing tack, I asked what where our chances of seeing the promised wildlife?

"The magnificent gelada, most definitely, the ibex probably, the wolf, well lets say 10%"

"And the leopard?"

Tesfay shook his head

"Ok we'll take the gelada, ibex and wolf, that'll do for us."

Tesfay laughed nervously at our British humour.

With a short acclimatisation walk on the first day, we set off from Sankaber Camp (3,230m) to Geech Camp(3,600m), an 8 hour 12km trek through giant heather forests, along towering ridges and through dusty farmland. The viewpoint overlooking the Genbar Falls was terrifying. Although dry at this time of year, the vertical 500m drop is unlike anything I have seen. Far below us black kites, falcons and lamergeyer vultures soared on the thermals.

The path up from the viewpoint marked our ascent into the higher altitude zone. Although short, the ascent was quick and at the altitude, punishing. Rather unfairly, enterprising villagers lurked with horses hoping to sell a ride up the hill. Like vultures they quickly identified the weakest link in the party and trailed closely. We proudly resisted, but many groups take the horses along for the whole trek to ease weary limbs.

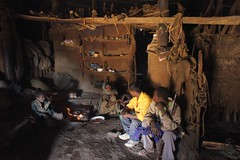

The trail eventually found the village of Geech. Simple rustic mud and thatch huts were surrounded by quick growing Eucalyptus and the ever bizarre Giant Lobelia. We were invited in for a coffee ceremony. Cultural ceremonies tend to ring alarm bells, but I was thirsty and stooped to enter into the gloom. Inside the hut the matriarch lit the fire. Eventually accustomed to the dim light I took in the surroundings. The interior resembled a museum recreation from the middle ages. The family slept on a raised slatted platform above their cattle. An open fireplace in the centre of the hut was the focal point. Despite the fire, the lofty conical roof meant it was relatively cool and smoke free. We sat on rocks draped in sheepskin and watched as the family prepared the coffee, roasting the beans over the open fire before grinding and adding to boiling water. There was nothing put on about this, it is simply the way they live. We tried some simple English on the teenage daughter. She was 14, went to school and had a basic grasp of English. I took her photograph and immediately her shyness was replaced by a coquettish smile. Almost before I had clicked the shutter, she ran to see the picture.

The trail eventually found the village of Geech. Simple rustic mud and thatch huts were surrounded by quick growing Eucalyptus and the ever bizarre Giant Lobelia. We were invited in for a coffee ceremony. Cultural ceremonies tend to ring alarm bells, but I was thirsty and stooped to enter into the gloom. Inside the hut the matriarch lit the fire. Eventually accustomed to the dim light I took in the surroundings. The interior resembled a museum recreation from the middle ages. The family slept on a raised slatted platform above their cattle. An open fireplace in the centre of the hut was the focal point. Despite the fire, the lofty conical roof meant it was relatively cool and smoke free. We sat on rocks draped in sheepskin and watched as the family prepared the coffee, roasting the beans over the open fire before grinding and adding to boiling water. There was nothing put on about this, it is simply the way they live. We tried some simple English on the teenage daughter. She was 14, went to school and had a basic grasp of English. I took her photograph and immediately her shyness was replaced by a coquettish smile. Almost before I had clicked the shutter, she ran to see the picture.

"Is beautiful" she proudly stated.

The second camp, Geech, is situated in a beautiful exposed spot on vast open grassland a couple of miles beyond the village. Tawny Eagles and Vultures perched menacingly on the few trees in the site. We stayed two nights at Geech to give ample time to explore the standout viewpoint at Imet Gogo and get used to the altitude. To picture Imet Gogo, imagine two dramatic ridge joining perpendicular at a raised corner. This rocky promontory is reached via an easy scramble across a narrow rock ledge. From the top, breathtaking 360 degree views open up. Never mind Kilimanjaro, this feels like the real roof of Africa. Below us, we watched two red billed chaf cartwheel like fighter jets locked into a dog-fight. 800m below them, the lowland foothills of the Simien Range lay studded with rock pinnacles and table mountains. It is a view that wouldn't look out of place at Bryce or the Grand Canyon.

That evening, we walked to Kedadit (3,760m) for the sunset. The haze burnt dusty orange over the lowlands and we watched as distant troops of baboons clambered over the edge and down to their cliff side caves. Ethiopia has an immense Christian heritage, and in scenery like this, it is not hard to see why religion has such a stranglehold on Ethiopian culture. Far below on a small isolated promontory, Adem pointed out his home. There were three or four huts and a smattering of livestock around each. To the naked eye there was no discernible way to get on or off the plateau.

That evening, we walked to Kedadit (3,760m) for the sunset. The haze burnt dusty orange over the lowlands and we watched as distant troops of baboons clambered over the edge and down to their cliff side caves. Ethiopia has an immense Christian heritage, and in scenery like this, it is not hard to see why religion has such a stranglehold on Ethiopian culture. Far below on a small isolated promontory, Adem pointed out his home. There were three or four huts and a smattering of livestock around each. To the naked eye there was no discernible way to get on or off the plateau.

On the way back to camp I asked Adem his story.

"I joined the army when the Derg were in power. After 5 years they were removed. Fortunately the new regime asked me to join up, flushing out bandits from the mountains" (The Derg were the oppressive socialist regime which replaced the Solomonic rule in the 70s).

"Was it peaceful after the Derg were forced out?"

"Mostly we tracked the shifta (bandits) in the mountains. They hid in caves and only moved around at night. We got information from villagers and would attack them in the dark."

I asked him how they had been affected by the famine?

"It was ok here. We didn't have to move. The main problem was more criminals, more shifta in the mountains. One day my brother was taken by the shifta. I followed them for three days. I got him back."

In a country where disputes between friends are often settled with violence, I drew my own conclusions as to what had happened that day. Later Tesfay told us how the locals traditionally use the sap from the Giant Lobelia trees to develop a poison. The poison was used to settle disputes with friends, with the recipient either dying or going crazy - the outcome was left to fate.

The nights on the plateau were cold, so we huddled inside the bare-bones kitchen at the camp-site for evening meals. The chef was a master at conjuring complex multi-dish meals with just one burner and pan. A typical meal consisted of soup, rice fritters, casseroled chicken legs, cabbage, beetroot, fried potatoes and boiled potatoes with onion, all washed down with surprisingly drinkable Ethiopian wine. Breakfasts of porridge, pancakes and bread were equally good. After a long day trekking we were invariably met with a steaming flask of tea and superb Ethiopian coffee accompanied by popcorn and roasted grain. All in all an unfeasibly gourmet affair.

The only thing missing was the local staple, Injurra. Injurra is a sour pancake made typically from the local Tej grain. It serves as plate, spoon and carbohydrate three meals a day, 365 days a year to most Ethiopians. In one bizarre creation, named Injurra Fir Fir, the Injurra is stewed until soggy then served upon another injura. Ethiopians loyalty to Injurra is unyielding, before most meals our guide and chef would pop out to the rangers hut for a quick fix of injurra before sitting down to eat with us. Its absence on the trek is probably a wise thing, as most foreigners are less than enamoured by its charms.

The next leg of the trail involved a 20km trek from Geech Camp to Cheneck Camp, over the peak at Inatye (4070m). Our first close sighting of Gelada Baboons came as we climbed the escarpment towards Inatye. We caught on to the tail end of a troop as it disappeared down a steep gully. A handful stayed with us to pluck the last few roots on the ridge before appearing to plunge off the cliff edge. We hid behind rocks and stalked them as cautiously as we could. Inatye itself is a terrifying promontory with sheer drops either side, translated it means something similar to mama mia, and the name does it justice. We ate our picnic carefully that day.

After the windswept solitude of Geech Camp, the third and final camp at Cheneck came as a surprise. There are more trekkers and more locals around but still Cheneck shines. The views are outstanding, stretching over Inatye and Imet Gogo and it is a magnet for wildlife. We were beset by Gelada Baboons roaming the camp-site. Not to be outdone, a huge Ibex stag with long curved horns and a superb beard strolled right through camp oblivious to the David Attenborough wannabes following it with outsized SLRs. The profusion of relatively tame wildlife mocked our amusing stalking tactics earlier in the day.

After the windswept solitude of Geech Camp, the third and final camp at Cheneck came as a surprise. There are more trekkers and more locals around but still Cheneck shines. The views are outstanding, stretching over Inatye and Imet Gogo and it is a magnet for wildlife. We were beset by Gelada Baboons roaming the camp-site. Not to be outdone, a huge Ibex stag with long curved horns and a superb beard strolled right through camp oblivious to the David Attenborough wannabes following it with outsized SLRs. The profusion of relatively tame wildlife mocked our amusing stalking tactics earlier in the day.

On our final day we climbed Mount Bwahit (4,430m). Bwahit is high, but it isn't Ethiopia's highest. That mantle belongs to the nearbye Ras Dashen. We had bottled out on doing Dashen a long time before getting to Ethiopia. It has a reputation as a bit of a dusty slog with countless false summits. Bwahit though is a different beast. Just a 4 hour climb from Cheneck Camp, it offered great views from the summit and the promise of good wildlife. We set out at 7am, the air chilly with the sun still hidden behind the peaks. The route passed along a dirt road for the first hour and we had to hop to the side as the occassional Isuzu lorry thundered down in clouds of dust. It wasn't long though before we struck lucky. Just 50m away across the stream were two endangered Ethiopian wolves. With only 400 in Ethiopia and 40 in the Park, this was an incredibly rare encounter. Unfortunately, to my un-educated eye they looked more like big foxes than wolves. As we walked away, perhaps keen to prove their wolf like qualities, the pair gave an incredibly chilling howl that reverberated around the valley. More treats were in prospect. The path soon found the ridge again and framed in the magnificent view were Ibex, lots of them. Buoyed by our luck, we pushed on to the summit. After ascending almost 1000m in height in two hours we pushed through the easy scree and summited. It was the perfect end to the trek.

At the moment, the park receives only 6,000 trekkers but the linear nature of the trail is a worry. During our visit the camp-sites were comfortable with no more than 10 tents at any site. During the peak January to December period, there can be up to 50 tents in each site. So whilst guides do their best to stagger morning starts expect busy trails and viewpoints. For the moment, I'd recommend you plan to time a visit during the quieter months of September, October and November when the grass is green and the air is clear or alternatively February, March and April. The summer months of June to October are also quiet, but expect rain, lots of it. For the future, hopefully more trails and camp-sites will be introduced in the Park.

At the moment, the park receives only 6,000 trekkers but the linear nature of the trail is a worry. During our visit the camp-sites were comfortable with no more than 10 tents at any site. During the peak January to December period, there can be up to 50 tents in each site. So whilst guides do their best to stagger morning starts expect busy trails and viewpoints. For the moment, I'd recommend you plan to time a visit during the quieter months of September, October and November when the grass is green and the air is clear or alternatively February, March and April. The summer months of June to October are also quiet, but expect rain, lots of it. For the future, hopefully more trails and camp-sites will be introduced in the Park.

With the trek over we only had to make our way back to Gonder, which is easier said than done. Desperate for a hot shower and clean clothes we had to endure 5 hours of typically bone rattling roads and choking dust first. Never before has such a feeble shower been so warmly welcomed.